Postcards from the Ice Age

Michael Hofferber © 1992 All rights reserved.

Eight times in the last million years Earth's climatic patterns have shifted dramatically, turning much colder in northern latitudes and allowing snow to linger year-round instead of melting off each summer. The snow compacted into ice, and the ice built up into glaciers and ice sheets that planed and scoured and scarred the land as they spread across much of Europe, Asia and North America.

The last of these "Ice Ages" concluded about 10,000 years ago. Glaciers that once extended as far south as the Ohio River Valley retreated into the highest mountains and far into the Arctic Circle. Behind them they left deep lakes, bowl-shaped valleys, and craggy peaks.

Only geologists seem to dwell much on ice ages, but at Glacier National Park in northwest Montana they are more than just a memory. Here, perhaps more than anywhere else in the world, the full force of their passage is engraved in the land. From the 48 remnant glaciers that cling to its chiseled mountains to the grizzly bears that roam its forests and the northern pike that swim its lakes, the million-acre park reflects an age most of the earth has covered over and forgotten.

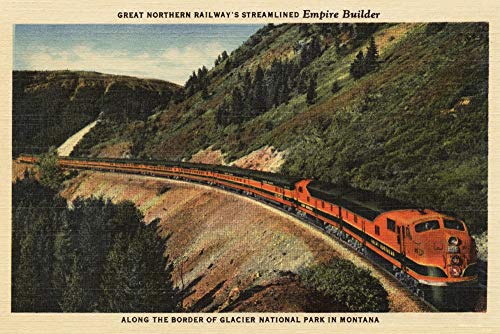

Established in 1910, Glacier National Park was endorsed by conservationists like George Bird Grinnell who wanted to preserve the area's natural wonders and the Great Northern Railroad which wanted to exploit them through tourism.

"Here is a land of striking scenery, the Crown of the Continent," Grinnell wrote in a 1901 issue of The Century Magazine. "No words can describe the grandeur and majesty of these mountains, and even photographs seem hopelessly to dwarf and belittle the most impressive peaks."

The Great Northern spent $1.5 million in early-century cash building a series of huge lodges, Swiss-style chalets and tent camps in and near the park, each a day's horseback ride apart. The railroad wanted visitors to book passage on its trains and spend week-long vacations in the park hiking, fishing and riding horses. Glacier quickly became one of the most visited and talked about treasures in the National Park System.

Amtrak has long since replaced the Great Northern's passenger train service and motorists now outnumber horseback riders by a large margin, but the grand old lodges still remain and the scenery is no less stunning.

At East Glacier, where Amtrak has its station, the venerable Glacier Park Lodge stands resolute. In its cathedral lobby whole trunks of Douglas fir rise up 40 feet from the floor, their ruddy bark still intact, and hold up the rafters. These trees greatly impressed the native Blackfeet Indians who pitched teepees on the hotel's grounds during its opening in 1913 and danced in celebration. They named the hotel "Oom-Coo-La-Mush-Taw" -- The Big Tree Lodge.

Equally impressive are Many Glacier Hotel on the shore of Swiftcurrent Lake and Lake McDonald Lodge with its timber-beamed ceilings and huge stone fireplaces. Every window seems to afford a view of glaciers and mountains and crystal-clear lakes.

In the backcountry, two rough stone chalets await adventurous hikers at the end of their treks. Situated four hours from the nearest road, the Sperry Glacier and Granite Park chalets offer dormitory-style lodging and simple meals. Since all supplies arrive on foot or by pack train the conditions are rustic, but both chalets are often completely booked months in advance of the summer hiking season.

Every lodge and chalet is linked to Glacier's vast network of well-marked trails which wind over 713 miles through the park and connect to another 200 miles of trail in Canada's Waterton Lakes National Park to the north. Easy day hikes lead to the impressive Grinnell Glacier from Many Glacier Lodge and to the thunderous Running Eagle Falls from the camp store at Two Medicine. Longer treks, like the Hanging Valley Walk or the Highline Trek along the Continental Divide provide opportunities for sighting bald eagles, bear, and mountain goats.

Glacier Park naturalists lead guided hikes and boat trips daily beginning in mid-June. For longer trips, private outfitters are available to plan and guide custom journeys. Wilderness campsites scattered throughout the park make backpacking convenient.

Glacier is "Bear Country," as prominently posted red signs announce at every campground and trail head. At least 200 grizzlies and nearly 500 black bear roam the majestic forests and quiet valleys of the park and they can be menacing. A few visitors and park employees have been mauled over the years, but precautions like wearing a bell when you hike in the backcountry and keeping odorous food locked up tight prevent most close encounters.

There's more wildlife to see than just bears, of course. Mountain goats and bighorn sheep reside on Glacier's towering snow-capped peaks. Moose and elk and deer frequent its meadows. Bald eagles soar with hawks and osprey in the skies overhead. Beaver and river otters swim in its streams.

Hunting is prohibited within Glacier's boundaries, as it is in all national parks, but fishing is allowed. A special fishing permit, available free of charge at ranger stations, is required. The park has 1,606 miles of potential trout streams and 653 lakes, but some waters are barren. Ask a ranger when in doubt.

Some of the most reliable fishing holes include Swiftcurrent, Josephine and Grinnell Lakes near Many Glacier Lodge, and Gunsight Lake at the end of a five-mile hike. Northern pike lure anglers to Sherburne Lake while Dolly Varden and cutthroat trout are the favorite catch on the North Fork lakes in the park's northwest corner. Motorboats are allowed on most of the larger lakes and canoes almost anywhere. Canoeists are especially fond of Bowman and Kintia lakes, both over six miles long and loaded with wildlife along the shoreline.

Another good way to get around in Glacier is on horseback.

Guided trail rides are available at Many Glacier, Lake McDonald Lodge, and Apgar. Private stock are allowed, but with restrictions.

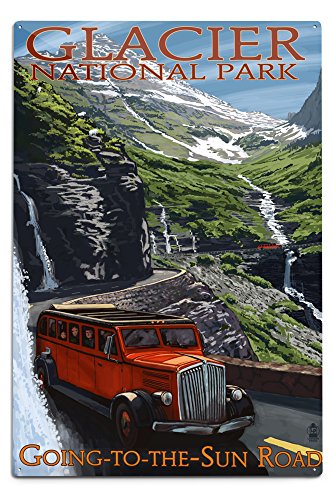

For those who enjoy touring by car or motorcycle, the Going to the Sun Road which bisects the park from east to west is a spectacular experience. Just 52 miles long, the roadway is full of twists and turns and stunning overlooks, requiring at least a couple hours to navigate. It cross the Continental Divide at Logan Pass, elevation 6,646 feet, where snowbanks linger until mid-June.

Restored 1936 touring vans carrying up to 16 passengers make day trips up the Going to the Sun Road from each of the park lodges between June and September. Originally built by the White Motor Company, the touring vans are bright red with open tops and cut a fine picture as they cruise through the icy passes. Locals have nicknamed them "jammers" after the drivers who used to double-clutch going over the mountains, but the vans now have automatic transmissions and power steering.

There are also helicopters rides available for aerial tours of the park and groomed cross-country ski trails open to visitors in the winter.

However you approach it, Glacier National Park is so broad and awesome that everyday worries quickly disappear, swallowed up in the primeval grandeur of blue-white icefields, pyramid-shaped peaks, and free-roaming beasts. As John Muir, the famous naturalist, once said of days spent at Glacier: "The time will not be taken from the sum of your life. Instead of shortening, it will indefinitely lengthen it."