Glenn Simmons. Copyright © Michael Hofferber. All Rights Reserved.

"Survivalists" in southern Oregon, convinced that our country is on the verge of an economic collapse and that a nuclear confrontation is inevitable, have been stockpiling weapons and rations in preparation for the chaos and madness that will follow. They spend hours each day cleaning and practicing with their guns, readying themselves for the killing they foresee, the violence no one can divert once the society begins to crumble and fall apart. Tons and tons of food goes underground, hoarded in caches and fallout shelters, in secret tunnels and passageways, where only a chosen few will know its location, where only a chosen few will be able to share.

Talking to some of the residents at Lee's Camp, 24 miles east of Tillamook on the Wilson River Highway, you will hear the same concerns - an uncertain economy, too much government, the threat of war.

These people, like their southern counterparts, are stockpiling too, only their vaults are being loaded with friends and knowledge, mutual assistance and wisdom.

Whether any of us would survive a nuclear holocaust, or what life would be like in this country after an economic collapse, is all conjecture. No one knows. In the meantime, though, life goes on. Children need raising, crops need tending, and bills need paying. We must work, we must eat, and we must have leisure.

The ways in which we do these things make up the quality of our lives, here and now.

The following is an account of the quality of life in Lee's Camp - the story of its earliest settlers, the society it has fostered, the weather, the fishing, the silence, and the wisdom its people have (and are willing) to share. Whether its style of living, its survivalism, is more adaptable than any other remains to be seen.

Whether it is more satisfying and sane seems obvious.

Homesteading

The America of 100 years ago was a society in flux, a land full of changes and quests and dreams. The psychic scars of the Civil War were still festering inside its people and the westward expansion of our “Manifest Destiny" was in full swing. With the last of the Indian Wars passing into history and the first of several bad winters hitting the farmers on the plains, hundreds of the disenchanted, disenfranchised and disappointed traded in the known present for an uncertain future on homestead sites in the state of Oregon.

One such family of refugees were the Reehers, James and Jennie and their children. They left Kansas in 1887 after storms, bad luck and illness drove them away. They came to Oregon looking for new oppor-tunities, for work, and for a home. In the end, they became the first homesteaders in the area that is now called Lee's Camp.

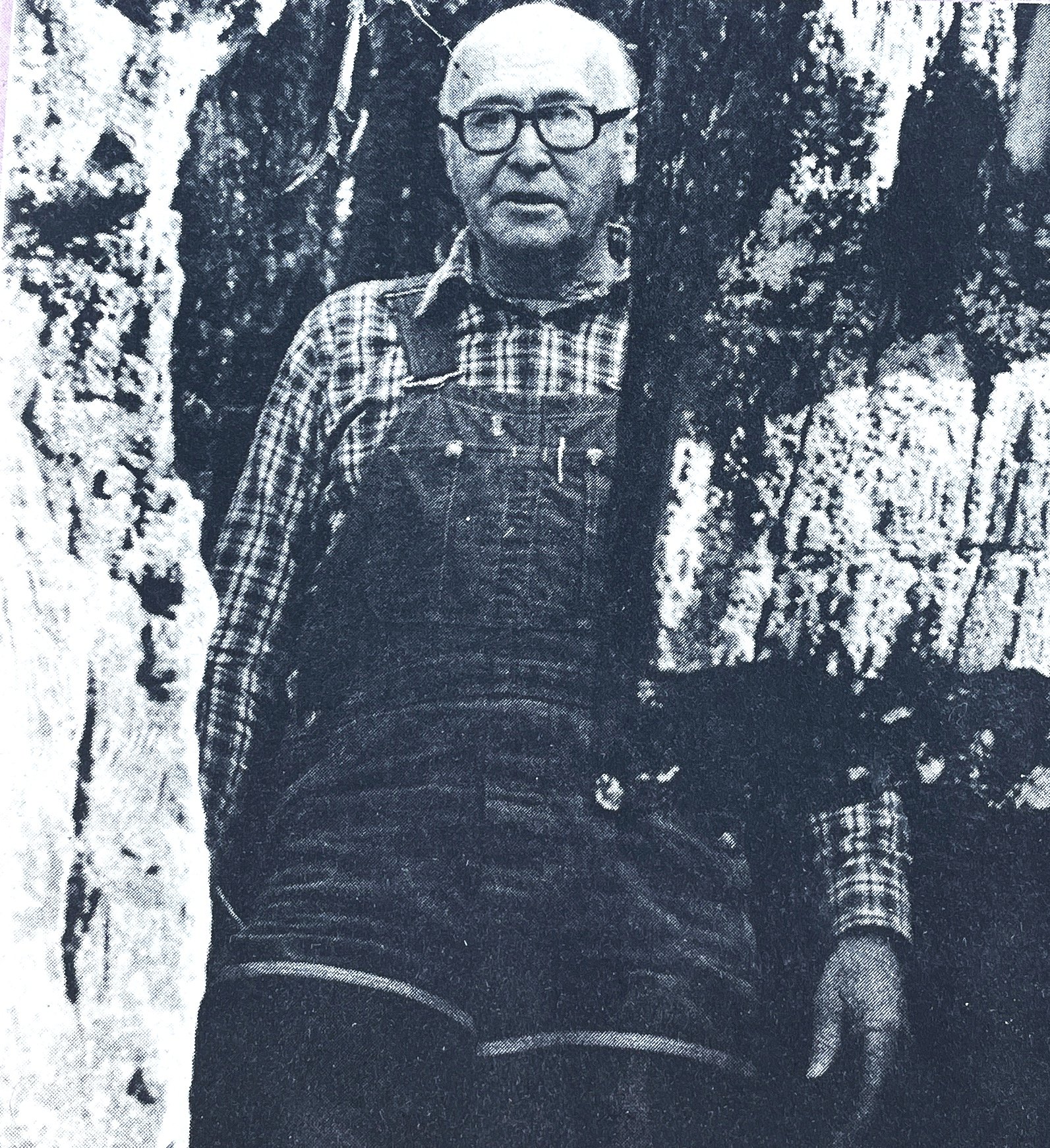

Kathleen Simmons, granddaughter of James Reeher, lives on the original homestead land today, with her husband Glenn. She has been gathering materials about the family's history for a geneology, and gladly shared the information she'd collected.

Her grandfather, Mrs. Simmons explained, got word in 1887 that the government was giving claims in Tillamook County. Reeher moved his family to Tillamook, where they lived and worked for a year until he'd picked out a homestead site, 24 miles up the Wilson River

Reeher’s Bridge. Copyright © Michael Hofferber. All Rights Reserved.

In the spring of 1889 Reeher went to the claim, slashed out 200 square feet of land, lived in the hollowed out trunk of a big fir tree until he had a cabin built and then, once the weather began to turn fair, moved the family up to join him.

There was no road to follow, only primitive trails, and the river had to be forded several times along the way. An expert packer, Bill Smith, was hired to guide them. Mrs. Simmons' grandmother, Jennie Reeher, described the experience in her journal:

"How clear it all comes back to me, that lovely April day in 1889. I can smell the fir trees and maples and hear the birds singing as plain as if it were yesterday.

"I was afraid when we forded the river and when the mule would go over a log. Those big logs lay across the trail and had been cut down barely enough for pack animals’ feet to get hold. We went over them with a great uprearing and down jumping that was certainly a shake-up.

It took two days to make the trip from Tillamook to the homestead. The family moved into the cedar-plank cabin and set up housekeeping. They brought along five hens and a rooster, and on a later trip they gained two cows. Soon there was milk and eggs to eat and, as the summer progressed, vegetables. The Reehers fished salmon from the river and hunted venison in the mountains, and were as self-sufficient on their land as any people before or since.

Other homesteaders and settlers followed the Reehers up the Wilson, making claims and building on sites of their own. Today the Simmons' live on a 370 acre tract of land which they share with four generations of Reehers descendants, who have 27 cabins and summer homes in the secluded and private mountain area.

Friends

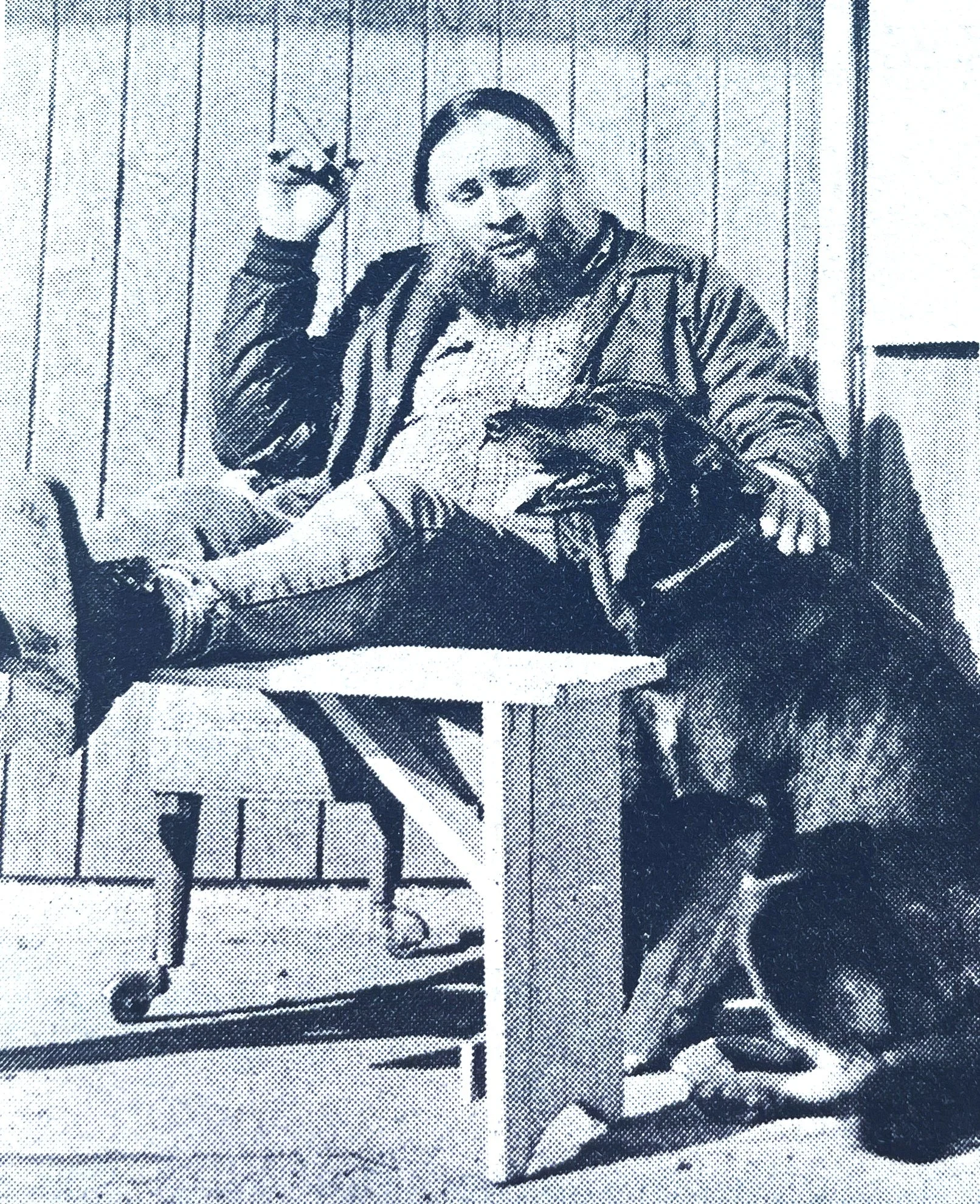

"After taxes the only things you have are the friends you make," said Bill Miles. He and his wife, Jeanie, own and operate the Lee's Camp store and filling station that sits next to the Wilson River Highway that connects Tillamook and Portland. Contrary to one's first impressions, they've discovered, there's a deep and tightly interwoven community functioning in this quiet, secluded forest outpost, one which they are only just now beginning accepted into.

Bill Miles and Free. Copyright © Michael Hofferber. All Rights Reserved.

The Miles' took over the store, a rustic and quaint structure on the north side of the highway, last sum-mer. They've been serving snacks, beer, pop, tackle and gas to the fishermen, hunters, and motorcyclists who use them as a handy reference point, as well as the four dozen or so local residents who live the year around at Lee's Camp.

At first the "locals" were skeptical about them, they recalled. For the last five years or so the store hadn't been open regularly. Previous owners would leave without notice, ignore consistent hours, and be closed weeks on end. The Miles' had to prove themselves to be hard working and responsible.

Once they did, though, they found the people of Lee's Camp to be hospitable and helpful neighbors.

"All the guys up here are real individuals," Jeanie said. "They are really nice. They'll do anything to help you."

Working together and helping each other out is part of living in Lee's Camp, she pointed out. It costs $2.62 for a trip into town in their small economy car, so making frequent trips into the city an expense that few can afford. The residents, instead, contact each other when they are making a trip to town, asking if they can pick something up for them, deliver anything.

"It's a completely different situation from living in Portland," Bill pointed out.

"You learn to economize and you learn to work together," Jeanie said of living at the edge of the wilderness in a small settlement.

Today the Miles family and their store is an integral part of Lee's Camp. It is the one institution, lacking any other businesses, churches, or civic clubs, that brings this community together. The store serves as a central nervous system for the residents, since nearly everyone stops by at one time or another during the week to pick up supplies, leave messages, collect their mail.

Jeanie and Bill both agree that the best thing about living where they do and working in the position they are in is the people they run into. "It seems like every month there's a different group of people," Jeanie said.

Today the store is open from six in the morning until seven at night through the winter, and until eight at night through the summer and serves a wide variety of customers.

The winter is the slowest time of the year, with perhaps 50 people living at Lee's Camp and anglers and motorcyclists visiting on the weekends. During the summer and fall, though, all that changes. Upwards of 2,000 people camp, fish, hike, swim and hunt in the Wilson River drainage.

“During the hunting season there's like half an infantry division running around the hills out here," Bill said.

The Lee's Camp store used to house a restaurant at one time, and was a popular stopping point for travelers and outdoorsmen. The Miles would like to get back to those days. "It would be nice if we could be sort of universal," Bill said, "and have a little bit of everything.”

Rain

In the 1978 edition of Encyclopedia Britannica Glenora, Oregon is listed as being the state's wettest spot, receiving 129.47 inches of rain in an average year. Tillamook, for comparison, receives 90-95 inches per annum.

Look in your recently published atlas, however, and you'll find no mention of the place, no city, no township, no burg of that title. There is no mention of it. The name Glenora was applied, in 1898, to a weather station located 24 miles east of Tillamook near the old Wilson River wagon road. That weather station was operated by none other than Mrs. Jennie Reeher.

In 1930 Edward Miller of the Sunday Oregonian bylined an article about Mrs. Reeher and Glenora's rainfall. He'd read that the Coast Range community received more precipitation than any other point in the 48 states.

"Glenora. Never heard of it." he wrote in that September 14th issue. "One hundred and thirty-one inches of rainfall! Enough water, if collected at once, to drown a five-foot man standing on the shoulders of a six-foot man.

"Inquiries at the Portland weather office led to this information: That Glenora was midway between Tillamook and Forest Grove on the Wilson River road; that it was a tiny settlement in the mountains; and Glenora, in truth, was headquarters of the rain god Jupiter. Mrs. Jennie A. Reeher had kept the records from 1892 to 1916 because she enjoyed the work. The government merely had supplied the apparatus and had occasionally sent an inspector to check the accuracy of her records.”

The Weather Service was skeptical about Mrs. Reeher's reports of the astonishing amount of rainfall at Glenora, Kathleen Simmons recalled. “They thought she didn't know how to read it or something,” she said.

An investigator was sent to spend some time with Mrs. Reeher, and to check on her unbelievable totals. Making certain that the gauge was empty before retiring for the night, he slipped out before dawn in a downpouring rain to make a reading. Much to his surprise the instrument was full!

The investigator, now a believer in Mrs. Reehers' claims, left soon after that, Mrs. Simmons said, and the records remained intact.

The U.S. Postal Service, in 1896, refused to grant the name Glenora to the post office that Walter J. Smith, a former member of the Union army, established near the Reehers' land. It was too similar to Glenwood, the name of a community in nearby Washington County. The name Wilson was officially given to the post office, which lasted about 20 years.

In about 1939 Rex Lee bought approximately 16 acres of the Reeher land, which he developed into a tourist and sportmen's camp with the name Lee's Wilson River Camp. A post office established there in 1947 gave the place its present nomenclature, Lee's Camp.

Despite all these changes, though, and despite the fluctuations of land ownership and use, one thing remains the same. It rains a heck of a lot up there.

Hunting and Fishing

Inside the store at Lee's Camp there is a large scrapbook that the Miles' have filled with Polaroid snapshots of fish caught in the Wilson River and weighed in at the store. One of the most recent is a picture of Roger McCann of Beaverton holding the 30-pound steelhead he pulled out of the river on Feb. 25. McCann's catch is the largest in recent history on the Wilson.

"Fishing used to be a whole lot better," Bill Miles ad-mitted, but also noted that there are still two major steelhead runs that make the Wilson a renowned coastal river to anglers throughout the country.

The Miles', who sell licenses, sand shrimp, worms and salmon eggs in their store, guard a favorite fishing hole of theirs beneath the Reeher Bridge (dedicated by a plaque to James and Jenie). Any fish caught from that hole, they insist with mock seriousness, must be split half and half with them.

What they don't demand portions of are the elk and deer taken from the hills all around them during hunting seasons in the fall. They are too busy handling the traffic of customers pouring through their doors in that concentrated period. Thanks to the blessing of abundant game herds in the area, many of the best days of their fledgling business history have been made during the hunting season, as they sell beer, gasoline, and snacks in great quantities to the sportsmen.

Thankful for the wildlife as well are the Simmons', but for different reasons.

"I love to be able to have animals and not have to take care of them," Kathleen Simmons said. Her hus-band, Glenn, feeds many of the deer on their acreage by hand, as they've learned to recognize and trust his generous hand. He has a special relationship with the wildlife at Lee's Camp, Kathleen pointed out.

"We're kind of nuts about game preservation,"

Glenn admitted. He puts out three gallons of rolled barley every night for the deer and elk to feed on, and he has plans for seeding several patches of the land with grass for the deer to graze on.

One of Simmons' biggest gripes, though, is the infantry division (which Bill Miles referred to) that roams the hillsides in the autumn - huge four-wheel drive rigs (often equipped for spotlighting, high-powered rifles with high-powered scopes.

"Dammit," he said, "I just can't see people going out here and shooting everything in sight."

The Lee's Camp area, O.S.P. game officer Mike Caldwell pointed out, probably has fewer problems with poaching than almost any other highly used location in Tillamook County, primarily because of the attitude and the concern of the people in the area. The Simmons' and the Miles', and others like them in the community are protective of the wildlife resources they share, and they keep a watchful eye on visitors.

Simmons has found, as Caldwell and other game officers find every year, dead or severely wounded does shot out of season and left to waste once the hunter discovered his mistake. "When I pull the trigger, I know what I'm going to hit," he said, shaking his head at the senselessness of it all.

Knowledge

“I get the impression that people have been living in a vacuum for the past 20 years," said Glenn Simmons one afternoon in early March of 1981.

Glenn Simmons. Copyright © Michael Hofferber. All Rights Reserved.

Glenn, who will be 74 years old in July, and Kathleen, who just turned 73, are both direct descendants of American pioneer families, self-reliant people who knew what needed to be done and weren't afraid to work to get it done. Together they put together a two-volume set of books a couple years ago called "From the Ground Up" which detail the survival techniques used by the homesteaders of the last century and show how these skills and abilities are still applicable in today's modern world.

"You can make evervthing you can buy in the store," Kathleen said, showing off the home-made soap that she'd molded into decorative and colorful, as well as functional, bars.

As part of the promotion of their book, the Simmons" began teaching community college classes on homesteading for survival, until the classes took up better than five nights a week of their time. Students of all ages, hungry for the knowledge and the wisdom they offered, crowded into the classes and workshops, overflowing the rooms they were held in.

Why the interest? Why all the attention? "Because they know that self-sufficiency is the only way to go," Glenn said. "They've tried the other way all their lives and they haven't gotten anywhere. They realize there are going to have to be some changes made.”

One of the changes he sees that has to be made is the attitude people have toward the land. "For every bushel of wheat grown over 80 pounds of topsoil is lost in the midwest each year," he pointed out. Pointing to his own garden, he explained how the land can be nurtured and developed if a man is willing to work with nature rather than fight it, willing to learn how to make the land productive rather than wasting it.

"I would rather see 100 acres split up into five acre parcels where people could be eking out an existence from the land, than see one man on 100 acres and 19 people on welfare," Glenn said. "Large industry has taken away the right of a person to live a simple life.”

What the Simmons' (and others like them) are about is giving people back the tools for living that life, and showing them how to use them. They have taught. bread-baking and gardening, quilting and home construction. They've offered what was common knowledge just two generations ago, but seems lost today. Of the students who've taken their classes, 697 have graduated out of town and into the country. Not a one has moved back into town.

"We'd better start getting on the stick in this country, " Glenn said, foreseeing the rough times ahead that so many other prophets have spied. But although he and his wife keep a healthy stockpile of canned and frozen foods on hand and could live pretty much independently of the outside world if they had a cow, their survival is one of sharing, not hoarding. Their prescription for solving most of this country's problems is more work, not less, more community, not less.

"I can't see how there's any other way to go, " Glenn said.

Solitude

"You absolutely feel as though you were miles away from everything," Kathleen Simmons said of life at Lee's Camp.

The silence is complete, broken only by the songs of birds, the pattering of the rain, the soft steps of deer on wet leaves.

"It's just lovely weather up here," she said, disclaiming the first impressions one has of a place that receives 120 inches of rain in a year. On days when the valley to the east and the coastline to the west are both fogged in, she pointed out, they will often be enjoying bright warm sunshine.

"We get our rains too," she admitted, but it passes soon enough and the clear, warm days are worth the wait.

For the Simmons', who describe themselves as "nature lovers," Lee's Camp is the perfect home. Here they can go hiking through the hills and the mountains. They can watch the salmon spawning in the streams. They can go for a swim in their favorite swimming hole. And they can talk to the wild animals.

"If we had a cow we wouldn't ask anybody for anything," Glenn said.